The Beginning

Thick fog descended from snowy mountain tops at an unfathomable pace. Wagtails stopped pecking around and flew away. The bharals rushed from their grazing grounds to the misty havens. The sun had gone into hiding, and the tall mountains blocked the remnants of twilight from reaching us. Soon, the visibility would drop to zero. There was only the sound of a stream reverberating in the frosty air. Droplets of cold drizzle were rolling down my cheek. I carefully took each step on the treacherous ground strewn with boulders uprooted in a recent landslide. The long and arduous trek had made me weary. There was no option of going back at that juncture. The civilization was far away…

The mythical source of the Ganga is not easily accessible. A 15-km-long tiring and treacherous trek takes pilgrims and travellers from the nearest roadhead at Gangotri to the base camp for Gaumukh, which is the pout of the glacial system that feeds the Bhagirathi River. The entire trekking path lies within the Gangotri National Park, which extends to the Chinese border. Long-term scientific studies have shown that the Gangotri Glacier lost 2.3 lakh square metres area between 2001 and 2016, and the rising temperatures could fasten this process, leading to catastrophic impacts. Bhagirathi is one of the two source streams of the Ganga, the other one being Alaknanda. While cultural beliefs attribute the source status to Bhagirathi, Alaknanda is Ganga’s source stream hydrologically. Several dam projects are at various stages of implementation downstream of these source rivers. The execution of such projects, often without long-term environmental impact assessments, has attracted criticism from environmental organisations.

A man naps while waiting for the boat to travel across the Tehri reservoir. Several villages were submerged or reduced into islets after the commissioning of the Tehri Dam. Even though most of the local people relocated to distant places, a few others cling to the isolated parcels of land remaining above water. The free boat service provided by the dam management is the only means of transport for these villagers in this region of the Tehri Garhwal district, Uttarakhand.

known as the yoga capital of the world, Rishikesh attracts thousands of tourists from abroad, many of them opting to extend their stay here due to its pleasant climate and liberal outlook. The image shows wandering sadhus and cattle sharing a night shelter in Rishikesh.

A visitor at the abandoned ‘Beatles Ashram’ near Rishikesh. Originally converted from a pristine forest into a yoga retreat by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1961, this place rose to fame after the Beatles stayed here to learn Transcendental Meditation from Yogi. The Ashram was abandoned later and is now a part of the Rajaji National Park and Tiger Reserve.

A pundit counts the coins a woman offers in Haridwar, the first important pilgrim centre on the Ganga. Millions of people from across India visit Haridwar to conduct rituals for the emancipation of the souls of their departed relatives. It is in this crowded city that the Ganga finally leaves its mountain home and enters the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

The cremation ground on the banks of the Ganga in Garhmukteshwar, Uttar Pradesh. This place was a centre of the widow sacrifice, Sati, before the colonial rulers banned it.

Pilgrims throng the riverbank in Garhmukteshwar. Due to its proximity to Delhi, this town attracts a steady flow of visitors throughout the year.

A man talking to the river and winds on the banks of Ganga at Farukhabad; a man who arrived to attend a funeral takes a bath in the Ganga at Kannauj.

The Ganga is most polluted when it reaches the industrial city of Kanpur, which is a hub of the leather industry. On one side, it provides livelihood to thousands and on the other side, it generates millions of litres of toxic waste, a big part of which finds its way to the Ganga despite numerous regulations and the construction of waste treatment plants. In recent years, there has been an encouraging reduction in the pollution levels in the river at Kanpur. It is not just the industries that pollute the Ganga. Copious amounts of waste end up in the water as part of the cultural practices of people, many of them still believing that the river can purify anything and everything.

A boatman in Prayag. Every year millions of pilgrims visit Sangam, the confluence of Ganga and Yamuna, and the mythical river Saraswati in Prayag. They take a boat ride to the middle of the water to offer prayers and flowers and to immerse the ashes of their parted ones. Considered holiest among the pilgrim centres along the Ganga, Prayag also hosts the Kumbh Mela, which is said to be the largest gathering of humans on earth.

Anand Bhavan, also known as Swaraj Bhavan, was the home of independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Converted into a museum, this palatial mansion in Allahabad (now renamed Prayagraj) has a rich collection of objects related to the life of Nehru.

The dried-up riverbed near the confluence of Ganga and Yamuna in Prayag where the Kumbh Mela is held. Besides being one of the most revered Hindu pilgrim sites, the ancient Prayag has a place in India’s Buddhist history. The adjoining areas of Prayag transformed into an urban centre after the Mughal emperor Akbar built a fort and founded the city of Allahabad (Ilahabad or ‘City of God’) near the confluence in 1583. The strategic fortification, which could be used to monitor and check the movement of troops from Calcutta towards Agra, Kanpur and Delhi, fell into the hands of the English East India Company in the second half of the 18th century. The fort eventually lost its strategic importance with the arrival of railways in the second half of the 19th century.

A man in the attire of Hanuman sits below a tree in Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh. Located on the southern bank of the Ganga, Mirzapur is famous for its carpet industry and the temples nestled in the Vindhya mountain range, which forms a natural barrier between the north and central parts of India.

For over 2,000 years Varanasi, which has several monikers such as Kashi and Banaras, has been a centre of pilgrimage, attracting people from across the world. Besides being an important pilgrim centre for Hindus, the city holds a special place for Buddhists. Gautama Buddha is believed to have delivered his first sermon circa 528 BCE at Sarnath on the outskirts of Varanasi

A firewood store near Manikarnika Ghat, the main cremation ground in Varanasi. Death or cremation in Varanasi is considered an assured path to heaven by many Hindus. Because of this belief, the Manikarnika Ghat is always lit with funeral pyres. People from the villages on the outskirts also bring bodies for cremation in Varanasi.

While the stamp of spirituality is visible throughout Varanasi, this city also offers a glimpse of the complex history of the Indian subcontinent. One of the oldest continuously inhabited urban centres in the world, Varanasi was a centre of religion, philosophy, trade and industry by the second mil lennium BCE. The arrival of Buddhism, which challenged the dominant Vedic practices, heralded a new era in the region. Beginning in the 12th century, another wind of change started blowing from the west, with the advance of iconoclastic Muslim rulers who destroyed several temples in the city. The situation somewhat reversed during the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar. However, the last powerful ruler of the Mughal dynasty, Aurangzeb, destroyed several temples here and built a couple of mosques. Many of Varanasi’s temples were revived in the later period, mainly sponsored by Maratha kings. The ripples of this chequered past often reflect on the whole of Indian politics. Compared to my earlier visit in 2011, I witnessed a sharper divide and distrust among the Hindus and Muslims living in the city in 2019. The ongoing dispute over the Gyanvapi Mosque is often used by opportunistic political parties to divide the communities further and gain electoral gains. While there are debates for and against ‘correcting the mistakes of the past’, it is undeniable that the fusion of cultures — whether it is food, architecture, textiles, music or spirituality — brought in by Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam, has made Varanasi a precious gem on the diverse platter that we call India.

Young men and boys take out a procession on the death anniversary of Dr B R Ambedkar, the champion of Dalit rights and father of India’s constitution, at Zamania near Ghazipur, eastern Uttar Pradesh. The state is home to the largest population of Dalits in India (around 4 crore as per the 2011 census) and often finds itself in the news for caste-based atrocities.

Due to its sheer size and economic importance, the Ganga influences the lives of millions living along its long and winding course. Boats of small and medium sizes continue to transport people and goods across the river at several places, including this village in the Ghazipur district.

Mustard fields and brick kilns filled the roadside as we proceeded through Bihar. Most of these kilns thrive on some form of bonded labour. Entire families, right from children to adults, stay around the place and work for 10 to 12 hours for paltry sums offered by the kiln owners. These photographs were taken on a cold and overcast day, somewhere near Lakhisarai.

An accidental exposure paints light rays on the frame of a lonely tree in the middle of a field outside Lakhisarai.

The bank of the Gandaki River, which originates near the Nepal-Tibet border and is a tributary of the Ganga, at Sonpur, Saran district, Bihar. Sonpur is famous for its annual cattle fair that attracts thousands of traders from across India and tourists from abroad.

Mules atop a hill in Munger, which is an important town and divisional headquarters on the banks of the Ganga in eastern Bihar. Munger was a major trade centre during the Mughal and colonial periods. The city and its surroundings are strewn with several monuments.

A farmer on the riverbed-turned-farmland in Bhagalpur, Bihar. The Ganga assumes a colossal size during the monsoon, attaining a width of several kilometres. Once the flood waters recede, the river exposes its fertile bed. People from faraway places flock to this ‘no man’s land’ for seasonal farming. Racing against time, they complete the harvest and leave before the river sweeps away everything.

The first image is of an abandoned Durga idol on the banks of the Ganga in Sahibganj, Jharkhand. Second image shows devotees of Lord Shiva making slow progress to the Deoghar temple in Jharkhand. This arduous pilgrimage involves crawling and walking alternately.

The first image shows a band of village musicians at a cremation ground in Rajmahal district, Jharkhand. At Rajmahal the Ganga bends sharply towards the south on its way to the Bay of Bengal. The river is so wide here that bridges across the river are a rare sight. People depend on boats and barges to commute across the river. We took a barge to cross the Ganga from Rajmahal to Manikchak, a small town in the Malda district of West Bengal. The hilly terrain of Rajmahal was of immense strategic importance during medieval times as the mountain passes here could be used to control the riverine traffic and the movement of troops. The second image is of a faqir who is travelling through a village in Jangipur district, West Bengal.

Boys play on the dry Ganga riverbed in Farakka, Murshidabad district. Farakka Barrage is the last barrage on the Indian side along the course of the Ganga. From here, the river enters Bangladesh and assumes a new name, Padma. The barrage diverts a fixed volume of water from the Ganga, based on a controversial water-sharing treaty, towards Hooghly on the Indian side and sends the rest to the neighbouring country. Padma eventually meets Jamuna (downstream of Brahmaputra) before merging with Meghna, which drains into the Bay of Bengal. The river system, comprising Hooghly, Padma, Jamuna and Meghna, along hundreds of small and medium-sized rivers, forms the Sunderbans Delta, the largest of its kind on earth. The second image was shot at Murshidabad, the seat of power of the Bengal Nawabs. The Bengali elite accepted colonial culture and English education open-heartedly and later revolted against the colonial powers. Old houses and palaces in the erstwhile power centres of Bengal still carry those memories.

Kolkata is the biggest city on the course of the Ganga. Developed as a fort and riverine port during the colonial period, Kolkata (old name Calcutta) had a meteoric growth, often stained with blood. Having failed to sustain the economic momentum in the globalised world of our times, it no longer holds the title of the most happening city in the country.

The first image is of a Bhojpuri movie playing out at a local movie hall in Kolkata. Not having the glamour of multiplexes, small theatres like this offer cheaper entertainment to daily-wage labourers and migrant workers. These movies, made at low budgets, often strengthen gender and socio-economic stereotypes and have cliche storylines. The second image is of a woman at the venue of protest against the contentious Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 by the central government, at Park Circus in Kolkata. Beginning from our entry to Uttar Pradesh, the journey was often under the shadow of uncertainty due to the widespread agitations against the controversial law. There were also numerous reports of police brutality against peaceful protestors. On some occasions, the protests turned into violent clashes between the opponents and supporters of the CAA, which makes the religion of the applicant criteria for granting citizenship and has been termed anti-constitutional by several rights organisations. A sense of tension was in the air when we entered eastern Bihar. At Munger, we found ourselves in the eye of a riot-like situation. There were moments we seriously thought of winding up the journey and returning to the safety of our homes. However, the atmosphere was calmed by the time we stepped into West Bengal, where large-scale agitations had been happening.

A closed industrial unit in Howrah. Kolkata and its twin sister Howrah used to be the industrial powerhouse of India. The skeletons of decaying factories like this tell the story of a foregone era.

A fish market in Kolkata. Fish is an inseparable part of Bengali cuisine, cutting across caste and religious barriers.

A fishing boat in the Hooghly near Diamond Harbour. Kolkata is the only riverine Major Port of India, with its survival tied to the water level in the Hooghly. The port is situated around 200km upstream from the Bay of Bengal and serves the interior of the Indo-Gangetic Plain and two Himalayan nations, namely Nepal and Bhutan.

Gangasagar Mela is one of the largest religious congregations in India. Almost three million people gather at Sagar Island on the occasion of Makar Sankranti to take a dip at the confluence of Ganga and Sagar (Bay of Bengal). There is a saying, ‘Sab tirath bar bar, Gangasagar ekbar (All other pilgrimages many times, Gangasagar only once)’. The popular belief that people should make this pilgrimage towards the end of their lives is not the only reason that makes this saying apt. Pilgrims have to struggle to make it to Gangasagar and return. The rush of more than three million (30 lakh) people within three or four days makes the pilgrimage a logistical nightmare for authorities. Besides, the ferry can operate between the mainland and Sagar Island only during high tide. Passengers have to impatiently wait in long lines for several hours to catch even a glimpse of the jetty.

Sundown over the Bay of Bengal on the eve of Makar Sankranti, at Sagar Island, West Bengal.

The End

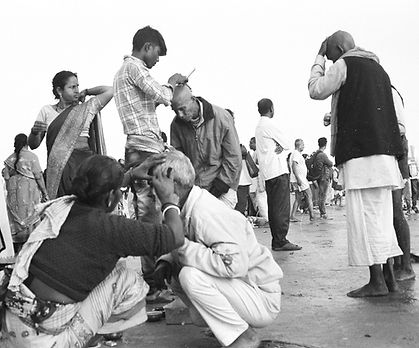

Silvery gentle waves washed my bare feet as I stood motionless, summoning the memories of the past few months. A pale curtain of red and purple hanging from above separated the day from the night. Surrounded by the vastness of burbling water, a sea of humanity wandered about the wet sand. Many among them tonsured their heads while others floated their offerings away to the expanse of water in the front. An intense feeling of having lost a dearer companionship filled my heart. The river had been a constant presence in my life for the last few months. There was hardly a day without an encounter with her in one way or another. Somewhere behind, she had found her destiny. I was yet to discover mine. I knew our tryst was coming to an end. The mood swings of the tidal waves, whether they were high or low, made it impossible to locate precisely the confluence of the river and the sea. I had a simple solution. At the beginning of our journey, I filled a small bottle with melted ice streaming out of the ice field. Three and a half months and 2,500km downstream, I pulled it out and waded through the waves. Standing in knee-deep water, I poured a few drops out of the bottle and watched them create tiny ripples below. The river and the sea became one. There was one more thing left in the itinerary. Filling my lungs with salty air, I took a dip. Cold water mixed with sand and sediments rushed from all sides, sweeping all the thoughts away.

In 2019, a couple of months after turning 33, I embarked on a journey along the banks of the Ganga River. The idea, proposed by my friend and journalist Sumit Usha in 2016, was to cover the entire length of the river on foot. However, immediately after starting the expedition, we realised that walking while carrying backpacks of around 20kg each wouldn’t be viable physically or economically. After hiking for a month along the mountainous stretch in Uttarakhand, we switched to cycling. The 2,500-km journey — spanning five states — took us through diverse geographical and cultural landscapes. Besides walking and cycling, we hitchhiked in trucks and tractors and travelled in trains, boats and barges. My friend Aditya Varma joined us for a considerable stretch, from Kanpur to Malda. Three-and-a-half months after starting from Gangotri Glacier,

we bid adieu to the river at Sagar Island, West Bengal, on the Hindu auspicious day of Makar Sankranti in January 2020.

First print edition in 2023 by

Albumen Books, New Delhi

© JOYEL K PIOUS